Humans are not the only species facing a potential threat from SARS-CoV-2, according to the results of a study by an international scientific team headed by researchers at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis). Using genomic analysis to compare the amino acids of a key part of the ACE2 protein that is used by SARS-CoV-2 to gain entry into human cells, with those of the ACE2 protein in more than 400 other animals, the team found it feasible that many different species, including some, like the Western lowland gorilla, which are highly endangered, could potentially be infected by the virus.

While the researchers caution not to “overinterpret” their results, which are based on computational models, they do suggest in their published paper that the findings could help to identify intermediate hosts for SARS-CoV-2 and “ … reduce the opportunity for a future outbreak of COVID-19.”

Harris Lewin, PhD, lead author for the study and a distinguished professor of evolution and ecology at UC Davis, commented, “The data provide an important starting point for identifying vulnerable and threatened animal populations at risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. We hope it inspires practices that protect both animal and human health during the pandemic.” Lewin and colleagues reported their findings in a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), which is titled, “Broad host range of SARS-CoV-2 predicted by comparative and structural analysis of ACE2 in vertebrates.”

Comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 and related coronavirus sequences has shown that SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 probably had ancestors that originated in bats, which was followed by transmission to an intermediate host, and that both viruses may have an extended host range that includes primates and other mammals, the authors wrote. “Many mammalian species host coronaviruses and these infections are frequently associated with severe clinical diseases, such as respiratory and enteric disease in pigs and cattle.”

Understanding the host range of SARS-CoV-2, as well as of related coronaviruses, will be key to improving the ability both to predict, and to control future pandemics,” they suggested. “It is also crucial for protecting populations of wildlife species in native habitats and under human care, particularly nonhuman primates, which may be susceptible to COVID-19.”

In humans, the main receptor for the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein is the angiotensin I converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is being intensively studied to understand transmission routes and sensitivity in other species, the investigators continued. ACE2 is found on many different types of cells and tissues, including epithelial cells in the nose, mouth, and lungs. “Comparative analysis of ACE2 protein sequences can be used to predict their ability to bind SARS-CoV-2 S and therefore may yield important insights into the biology and potential zoonotic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the team continued.

In humans, 25 amino acids of the ACE2 protein are important for the virus to bind and gain entry into cells. The researchers used these 25 amino acid sequences of the ACE2 protein, and modeling of its predicted protein structure, together with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, to evaluate how many of these amino acids are found in the ACE2 protein of the different species. “… we used a combination of comparative genomic approaches and protein structural analysis to assess the potential of ACE2 homologs from 410 vertebrate species (including representatives from all vertebrate classes: fishes, amphibians, birds, reptiles, and mammals) to serve as a receptor for SARS-CoV-2 and to understand the evolution of ACE2/SARS-CoV-2 S-binding sites,” they wrote. “Twenty-five amino acids corresponding to known SARS-CoV-2 S-binding residues were examined for their similarity to the residues in human ACE2.”

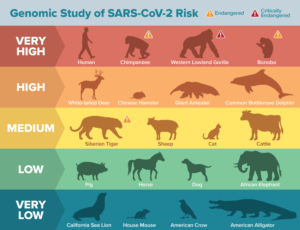

“Animals with all 25 amino acid residues matching the human protein are predicted to be at the highest risk for contracting SARS-CoV-2 via ACE2,” said Joana Damas, PhD, first author for the paper and a postdoctoral research associate at UC Davis. “The risk is predicted to decrease the more the species’ ACE2 binding residues differ from humans.”

The resulting data showed that about 40% of the species that may be potentially susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 were classed as “threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and may be especially vulnerable to human-to-animal transmission. Of these, several critically endangered primate species, such as the Western lowland gorilla, Sumatran orangutan, and Northern white-cheeked gibbon, are predicted to be at very high risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 via their ACE2 receptor. Other animals flagged as high risk include marine mammals such as gray whales and bottlenose dolphins, as well as Chinese hamsters.

In documented cases of SARS-COV-2 infection in mink, cats, dogs, hamsters, lions, and tigers, the virus may be using ACE2 receptors or they may use receptors other than ACE2 to gain access to host cells. Lower propensity for binding could translate to lower propensity for infection, or lower ability for the infection to spread in an animal or between animals once established. Because of the potential for animals to contract the novel coronavirus from humans, and vice versa, institutions including the National Zoo and the San Diego Zoo, which both contributed genomic material to the study, have strengthened programs to protect both animals and humans.

“Importantly, many threatened and endangered species were found to be at potential risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection based on their ACE2 binding score, suggesting that as the pandemic spreads humans could inadvertently introduce a potentially devastating new threat to these already vulnerable populations, especially the great apes and other primates,” the investigators stated.

“Zoonotic diseases and how to prevent human to animal transmission is not a new challenge to zoos and animal care professionals,” said co-author Klaus-Peter Koepfli, PhD, senior research scientist at Smithsonian-Mason School of Conservation and former conservation biologist with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s Center for Species Survival and Center for Conservation Genomics. “This new information allows us to focus our efforts and plan accordingly to keep animals and humans safe.”

The authors urge caution against overinterpretation of the predicted animal risks based on the computational results, noting the actual risks can only be confirmed with additional experimental data. “Importantly, our predictions are based solely on in silico analyses and must be confirmed by direct experimental data,” they acknowledged. “The prediction accuracy of the model may be improved in the future as more extensive data are generated … Until the present model’s accuracy can be confirmed with additional experimental data, we urge caution not to overinterpret the predictions of the present study. This is especially important with regards to species, endangered or otherwise, in human care.”

Research has shown that the immediate ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 likely originated in a species of bat. However, bats were found to be at very low risk of contracting the novel coronavirus via their ACE2 receptor, which is consistent with actual experimental data. Whether bats directly transmitted the novel coronavirus to humans, or whether it went through an intermediate host, is not yet known, but the study supports the idea that one or more intermediate hosts was involved.

The data could help researchers to home in on which species might have served as an intermediate host in the wild, assisting efforts to control a future outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection in human and animal populations. And as the authors concluded, “Our results, if confirmed by additional experimental data, may lead to the identification of intermediate host species for SARS-CoV-2, guide the selection of animal models of COVID-19, and assist the conservation of animals both in native habitats and in human care.”