Studies in mice by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown how the effects of a standard immunotherapy drug can be enhanced by blocking a protein called TREM2, resulting in the complete elimination of tumors. The results point to a potential new way to render immunotherapy effective for greater numbers of cancer patients.

“Essentially, we have found a new tool to enhance tumor immunotherapy,” said Marco Colonna, MD, the Robert Rock Belliveau, MD, professor of pathology. “An antibody against TREM2 alone reduces the growth of certain tumors, and when we combine it with an immunotherapy drug, we see total rejection of the tumor. The nice thing is that some anti-TREM2 antibodies are already in clinical trials for another disease. We have to do more work in animal models to verify these results, but if those work, we’d be able to move into clinical trials fairly easily because there are already a number of antibodies available.”

Colonna is senior author of the team’s published paper in Cell, which is titled, “TREM2 Modulation Remodels the Tumor Myeloid Landscape, Enhancing Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy.”

Immunotherapy that stimulates the patient’s own immune system to attack cancer cells has revolutionized cancer treatment. However, current immunotherapy drugs are effective for fewer than a quarter of patients, because tumors are notoriously adept at evading immune assault. T cells have the ability to detect and destroy tumor cells, but tumors can create a suppressive immune environment in and around themselves that keeps T cells subdued.

Checkpoint inhibition immunotherapy effectively triggers T cells to come out of quiescence so they can begin attacking the tumor, but when the tumor environment remains immunosuppressive, checkpoint inhibition alone may not be enough to eliminate the tumor. “Suppressive mechanisms directly affect T cell responses by engaging immune checkpoints such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death-1 (PD-1),” the authors explained.

Tumors also co-opt myeloid cells to suppress anti-tumor T cell responses, they continued. “… checkpoint blockade is incompletely effective for certain tumors, because they can escape using multiple mechanisms, one of which is the generation of a tumor microenvironment rich in myeloid cells with a strong immunosuppressive function … Myeloid cells constitute a significant cellular fraction of the microenvironment of many tumors and have been shown to inhibit T cell responses through multiple mechanisms.”

Scientists have recently focused on a subset of macrophages—a type of myeloid cell—that expresses the cell surface receptor TREM2. Colonna has long studied TREM2 in the context of Alzheimer’s disease, where the protein is associated with underperforming macrophages in the brain. Colonna and first author Martina Molgora, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher, realized that the same kind of macrophages also were found in tumors, where they produce TREM2 and promote an environment that suppresses the activity of T cells.

Colonna and Molgora—together with colleagues Robert D. Schreiber, PhD, the Andrew M. and Jane M. Bursky distinguished professor; and William Vermi, MD, an immunologist at the University of Brescia—then set out to determine whether inhibiting TREM2 could reduce immunosuppression and boost the tumor-killing powers of T cells. “When we looked at where TREM2 is found in the body, we found that it is expressed at high levels inside the tumor and not outside of the tumor,” Colonna said. “So it’s actually an ideal target, because if you engage TREM2, you’ll have little effect on peripheral tissue.”

The team first demonstrated that transplanted tumors grew more slowly in mice engineered to lack TREM2. Further analyses indicated that in these animals CD8+ T cells were more able to act against the tumor and may also have been more responsive to anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. The researchers then carried out a study to investigate the effect on tumor growth of directly blocking TREM2, in mice.

They injected cancerous cells into mice to induce the development of a sarcoma. These mice were then divided into four treatment groups. One group of animals received a monoclonal antibody (mAb) that blocked TREM2; a second cohort received a checkpoint inhibitor; a third were treated using both anti-TREM2 antibody and an anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor; and the fourth, control group, received a placebo.

The study results confirmed that the sarcomas grew steadily in mice that received placebo. In animals that received the TREM2 antibody or the checkpoint inhibitor alone, the tumors grew more slowly, plateaued, or in a few cases disappeared. In contrast, all of the mice that received both antibodies rejected the tumors completely. The researchers repeated the experiment using a colorectal cancer cell line, with similar results. “Altogether, these data suggest that mAb-mediated modulation of TREM2 drives the remodeling of the intra-tumor myeloid compartment in a manner that promotes a protective T cell response and enhances anti-PD-1 immunotherapy,” the investigators reported.

With the help of graduate student Ekaterina Esaulova, who works in the lab of Maxim Artyomov, PhD, an associate professor of pathology and immunology, the researchers analyzed immune cells in the tumors of the mice treated with the TREM2 antibody alone. They found that suppressive macrophages were largely missing and that T cells were plentiful and active, indicating that blocking TREM2 is an effective means of boosting anti-tumor T cell activity.

“This study demonstrates that constitutive lack of TREM2 or anti-TREM2 treatment curbs tumor growth and leads to complete tumor regression when associated with suboptimal PD-1 immunotherapy,” the scientists concluded, noting that the mechanisms by which either a lack of TREM2 or anti-TREM2 treatment impacts on tumor macrophages isn’t yet clear.

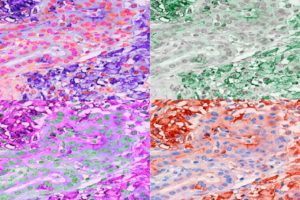

Further experiments revealed that macrophages with TREM2 are found in many kinds of cancers. To assess the relationship between TREM2 expression and clinical outcomes, the researchers turned to the Cancer Genome Atlas, a publicly available database of cancer genetics jointly maintained by the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute. They found that higher levels of TREM2 correlated with shorter survival in both colorectal cancer (CRC) and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). “Analyses of the TCGA database suggested that anti-TREM2 treatment may be particularly promising in CRC and TNBC, because TREM2 expression inversely correlated with overall survival and relapse in these cancer patients,” they suggested.

The researchers are now expanding their study of TREM2 to other kinds of cancers to see whether TREM2 inhibition might be a promising strategy for a range of tumor types. “Beyond these correlations, our extensive pathology study of human tumors suggests that TREM2 may be a particularly attractive therapeutic target, as it was highly expressed in the vast majority of over 200 cases of primary and metastatic tumors that we examined,” they stated. In contrast, TREM2 wasn’t highly expressed in normal tissues. “We conclude that reshaping of tumor-associated macrophages by anti-TREM2 mAb is a promising avenue for complementing checkpoint immunotherapy.”

“We saw that TREM2 is expressed on over 200 cases of human cancers and different subtypes, but we have only tested models of the colon, sarcoma, and breast, so there are other models to test,” Molgora said. “And then we also have a mouse model with a human version of TREM2.” Added Colonna: “The next step is to do the animal model using the human antibody. And then if that works, we’d be ready, I think, to go into a clinical trial.”