Diffuse, widespread, and chronic pain, such as that caused by fibromyalgia, is often frustratingly difficult to understand. Concentrating on the gut, however, may yield new insights. It may even simplify the diagnosis of notoriously hard-to-pin-down conditions. This would be welcome news to fibromyalgia patients, who can endure long waits—four to five years—before receiving a final diagnosis

The gut, or more particularly the gut microbiome, was the subject of a study that appeared June 18 in the journal Pain. According to this study, approximately 20 different species of bacteria were found in either greater or are lesser quantities in the microbiomes of study fibromyalgia patients than in the microbiomes of controls.

These microbiome differences were discovered by scientists based at McGill University. The scientists, in a paper titled “Altered microbiome composition in individuals with fibromyalgia,” declared that to the best of their knowledge, their study represents the “first demonstration of gut microbiome alteration in non-visceral pain.”

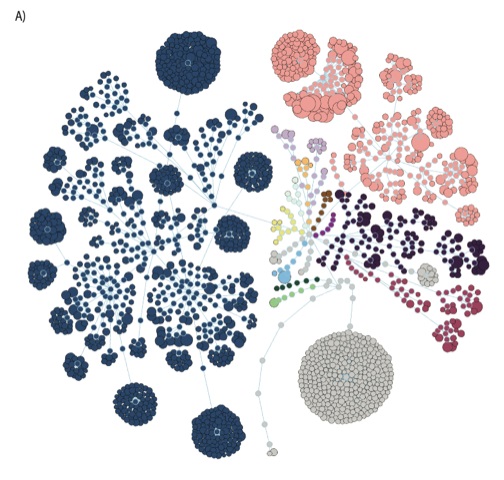

“Variance in the composition of the microbiomes was explained by fibromyalgia-related variables more than by any other innate or environmental variable and correlated with clinical indices of fibromyalgia,” the article’s authors wrote. “Using machine learning algorithms, the microbiome composition alone allowed for the classification of patients and controls.”

These findings were obtained after the McGill-led scientific team examined the microbiomes of 77 women with fibromyalgia and those of 79 control participants. To compare the microbiomes of the two groups, the scientists used 16S rRNA gene amplification and whole genome sequencing.

“We used a range of techniques, including artificial intelligence, to confirm that the changes we saw in the microbiomes of fibromyalgia patients were not caused by factors such as diet, medication, physical activity, age, and so on, which are known to affect the microbiome,” said Amir Minerbi, MD, PhD, clinical research fellow at the Alan Edwards Pain Management Unit, McGill University Health Centre and the first author of the paper. “We found that fibromyalgia and the symptoms of fibromyalgia—pain, fatigue, and cognitive difficulties—contribute more than any of the other factors to the variations we see in the microbiomes of those with the disease.

“We also saw that the severity of a patient’s symptoms was directly correlated with an increased presence or a more pronounced absence of certain bacteria—something which has never been reported before.”

At this point, it’s unclear whether the changes in gut bacteria seen in patients with fibromyalgia are simply markers of the disease or whether they play a role in causing it. Because the disease involves a cluster of symptoms, and not simply pain, the next step in the research will be to investigate whether there are similar changes in the gut microbiome in other conditions involving chronic pain, such as lower back pain, headaches, and neuropathic pain.

The researchers are also interested in exploring whether bacteria play a causal role in the development of pain and fibromyalgia—and whether their presence could, eventually, help in finding a cure, as well as speed up the process of diagnosis.

“We sorted through large amounts of data, identifying 19 species that were either increased or decreased in individuals with fibromyalgia,” noted Emmanuel Gonzalez, PhD, a bioinformatics specialist at McGill and a coauthor of the current paper. “By using machine learning, our computer was able to make a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, based only on the composition of the microbiome, with an accuracy of 87%. As we build on this first discovery with more research, we hope to improve upon this accuracy, potentially creating a step-change in diagnosis.”

“People with fibromyalgia suffer not only from the symptoms of their disease but also from the difficulty of family, friends, and medical teams to comprehend their symptoms,” stated Yoram Shir, MD, the senior author of the paper, the director of the Alan Edwards Pain Management Unit at the McGill University Health Centre, and an associate investigator from the BRaiN Program of the RI-MUHC. “As pain physicians, we are frustrated by our inability to help, and this frustration is a good fuel for research. This is the first evidence, at least in humans, that the microbiome could have an effect on diffuse pain, and we really need new ways to look at chronic pain.”