April 15, 2010 (Vol. 30, No. 8)

Single-Molecule Detection Solutions Push the Technique to New Levels

Third-generation (gen-3), single-molecule sequencing technology is not only about making quantifiable enhancements to second-generation (gen-2) capabilities, but also about improving data quality and expanding the types of data produced. “It is becoming clear that we will need information about the structure of genomes and other types of information to put the whole picture together,” said Stephen Turner, Ph.D., founder and CTO of Pacific Biosciences. This will include information about a variety of epigenetic modifications.

In Dr. Turner’s view, one of the advantages of the company’s technology is that “it unifies the previously separate fields of genomic and epigenomic research.” At present, research in the fields of developmental biology and oncology, in particular, would greatly benefit from this synergy, observed Dr. Turner.

The Single Molecule Real Time (SMRT™) sequencing technology that Pacific Biosciences unveiled at the recent “Advances in Genome Biology and Technology” (“AGBT”) conference generates both DNA sequence and epigenomic information directly from the real-time sequencing of genomic DNA. Single-molecule sensitivity enables faster results and longer read lengths, Dr. Turner asserted.

“Read length is extremely important for understanding the structure of the genome,” he added. “It is, perhaps, the dominant force driving the transition from microarrays to sequencing applications in personalized medicine.” Being able to detect and understand changes in the structure of individual genomes as they relate to disease—the presence of nucleotide duplications, inversions, deletions, etc.—may reveal a lot more about how people differ than single-base changes can.

SMRT DNA sequencing technology eavesdrops on the actions of a single DNA polymerase molecule as it works its way along a DNA template synthesizing a new complementary strand. “The technology allows us to see the kinetics of every base incorporation,” Dr. Turner said. In addition to generating sequence data, the process provides direct epigenetic information based on the effects that various base modifications have on the kinetics of the sequencing reaction.

Within about two years, the company plans to offer an application that will enable direct RNA sequencing in real time on the SMRT system without the need to convert RNA to cDNA. This application will provide insights into the “epigenetics of RNA,” said Dr. Turner, citing an example presented at the conference in which RNA sequencing using SMRT technology could distinguish pseudo-uridine from its native analog.

The company is already disseminating its vision for version 2 of the SMRT DNA sequencing system, scheduled for release in 2014. It will offer higher sensitivity and faster resolution, “will be highly portable and will be able to sequence a human genome in 15 minutes for less than $100,” added Dr. Turner.

With single-molecule sequencing (SMS), “the technology will no longer be a limitation to the application of genomic data for clinical decision making,” said Patrice Milos, Ph.D., vp and CSO at Helicos BioSciences, noting, however, that a clear understanding of how to apply this information in a medical setting is still, in general, emerging.

At the “AGBT” meeting, Dr. Milos offered a vision of genome biology that will be achievable through a combination of sequence and quantitative data. It will enable a range of applications including chromatin profiling by direct sequencing of immunoprecipitated DNA, direct RNA sequencing, small RNA quantitation, digital gene expression, copy number variation assessment, and epigenetic analysis.

Helicos has pioneered gen-3 sequencing with its True Single Molecule Sequencing (tSMS™) technology, a sequencing-by-synthesis technique. tSMS technology allows researchers to analyze nearly a billion molecules at the single-molecule level in one experiment, according to Dr. Milos. In addition to sequencing DNA, it can be used for direct sequencing of RNA without the need for a cDNA intermediate, thereby eliminating cDNA synthesis-based artifacts.

Life Technologies recently introduced its new gen-3 system that performs SMS directly on the surface of a 10 nm quantum dot nanocrystal. This method is “complementary to and not competitive with” second-generation methods, said Joseph Beechem, Ph.D., CTO at Life Technologies.

Gen-2 technology is well suited for genomic discovery and unraveling the genetic basis of disease. Over the next three years, Dr. Beechem predicts that as many as one million human genomes will be sequenced using these methods, giving researchers the information needed to link specific genes with disease predisposition and a range of human disorders.

“Gen-3 sequencing technology will then make it possible to start applying these discoveries in the clinic to guide medical decisions.” Dr. Beechem emphasized the need for long, continuous read lengths to enable some medical applications, such as haplotype phasing in which an allele of interest is identified as belonging to either the maternal or paternal DNA strand. This has important implications for predicting immunological responses, drug metabolism/sensitivity, cancer progression/metastasis, genomic structural variations, and other medically relevant genetic effects.

In his presentation at “AGBT”, Dr. Beechem described how the quantum-dot SMS technology enables several new sequencing capabilities. Conceptually, it is as though a movie camera (i.e., the quantum dot) were mounted on a DNA polymerase molecule, filming the DNA sequencing reaction in real time along a single DNA strand as it would occur in nature. All of the action being captured on film—the simultaneous, parallel sequencing of about 150,000 DNA strands—takes place in one field of view of the microscope.

“Since the sequencing engine is a ‘replaceable’ reagent, continuously tunable long reads and tunable accuracies can be realized by simply washing-in new sequencers to replace the older ones as they ‘wear out’ inside the microscope,” Dr. Beechem explained. The detection field tracks with the moving polymerase so sequence data is collected in real time.

“It follows the polymerase wherever it goes, allowing sequencing reactions to be performed in a wide variety of formats in addition to standard arrays (for example, flowing channels, tissue slices, sample surfaces). Each genomic DNA template is sequenced multiple times. The technology relies on Qdot® nanocrystals composed of inorganic materials (semiconductors) that provide 100-fold greater absorbance than a typical organic dye and generate about a 200X stronger fluorescent signal,” said Dr. Beechem.

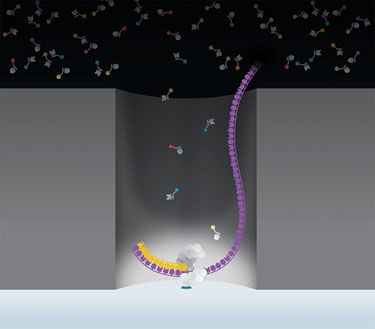

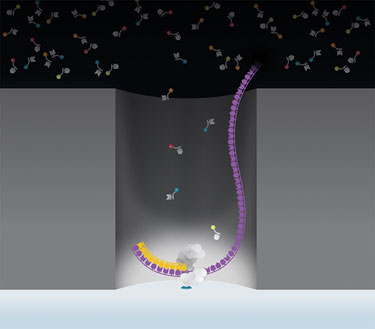

Pacific Biosciences’ sequencing process uses SMRT Cells, each of which contains thousands of zero-mode waveguides (ZMW). A single DNA polymerase molecule is attached to the bottom of each ZMW, which provides a real-time observation window of a single molecule of DNA polymerase as it synthesizes DNA.

Real-World Results

A paper published online in March in the New England Journal of Medicine describes the use of Life Technologies’ SOLiD™ System to perform whole-genome sequencing, resulting in the identification of the genetic mutation associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, an inherited neurological disorder that impairs motor and sensory nerve function. The SOLiD system is an example of amplification-based gen-2 sequencing technology.

Researchers at the Institute for Systems Biology relied on the genome sequencing services of Complete Genomics to sequence the genomes of four members of a nuclear family in which the two children have Miller syndrome and ciliary dyskinesia, a recessive genetic disorder that causes lung disease similar to cystic fibrosis.

The company sequenced the four genomes to a depth of 51X to 88X, making a call on 85%–92% of the bases. Comparative analysis of the four genomes led to the identification of four genes consistent with recessive inheritance of rare variations, and one of these genes, called DHODH, was concurrently identified as the cause of Miller syndrome, a finding published in Nature Genetics.

“Last year at ‘AGBT’ we presented our first sequenced genome,” recalled Rade Drmanac, Ph.D., Complete Genomic’s CSO. “During that year we sequenced more than 50 genomes.” For 2010, the company’s goal is to sequence 5,000 genomes. Earlier this year, it sequenced eight genomes for a customer for a total price of $160,000, or $20,000/genome, and that price continues to drop. “We will get to the point where the cost of sequencing will not be a limiting factor for large studies,” said Dr. Drmanac. The company’s business model centers on providing a large-scale human genome sequencing service for genomics researchers.

The company’s sequencing technology is based on self-assembling DNA nanoarrays and ligation-based sequencing. When developing its technology, Complete Genomics intentionally steered clear of single-molecule detection methods, noted Dr. Drmanac, in order to keep both the cost of sequencing and the error rate as low as possible. Yet the company sought to build in some of the advantages that an SMS format offers. The result was a high-density rectangular nanoarray in which 200 nm diameter DNA spots, separated by a distance of 0.7 microns, are arrayed on a silicon chip. About three billion DNA spots can be arrayed on a single 1 inch x 3 inch chip in a precise grid.

The company developed a method for amplifying short (200–300 base) single-stranded fragments of circularized genomic DNA templates in solution using a traditional enzymatic reaction. This rolling circle replication strategy produces a concatamer of as many as 500 copies of the DNA fragment in one long strand. To prevent these molecules from becoming entangled as they increase in length, Complete Genomics devised a strategy by which the pallindromic sequences present along each DNA chain fold back on each other as the replication progresses, forming a nanoball. These DNA nanoballs are about 200 nm in size and are highly polar particles that naturally repel each other in solution.

“In 30 minutes, a 1 mL sequencing reaction can create up to 50 billion DNA nanoballs, each composed of 500 copies of a genomic DNA sequence,” noted Dr. Drmanac. “We then flood the surface of a silicon chip with the solution of DNA nanoballs and they self-assemble into grids, with one nanoball per spot.” A single chip will contain enough amplified DNA to sequence an entire genome.

The fluorescent signals emitted from the chip are detected with a CCD camera. “We are currently able to measure a DNA spot using two pixels,” added Dr. Drmanac. The detection efficiency of the system will continue to increase as camera speeds improve.

Following the introduction of its first Genome Sequencer™ (GS) System—the GS 20—nearly five years ago, 454 Life Sciences, a Roche company, brought the GS FLX System to market in January 2007. Now, during the second quarter of this year, the company will launch the GS Junior System, a smaller, lower-cost version of the GS FLX.

Christopher McLeod, president and CEO of 454, described the benchtop GS Junior as “the personal computer for life sciences.” It has a throughput of >35 million bases per run, with a run time (including sequencing and data processing) of 12 hours. Average read lengths are 400 bases, with 99% accuracy. In addition, later this year the company plans to announce increased read-length capability of up to 1,000 bases for the GS FLX System.

The 454 sequencing technology is a high-resolution, high-throughput genotyping tool, and the company intends to move it into the clinical setting for diagnostic applications in the future. Applications would include infectious-disease diagnostics, identification of drug-resistant variants of HIV, or detecting one or more alleles or sets of genes associated with a particular medical disorder.

At “AGBT”, Henry Erlich, Ph.D., director of human genetics and vp of discovery research at Roche Molecular Systems, described an application in which the GS FLX was used for human leukocyte antigen typing. The GS FLX is also currently being used for emerging pathogen surveillance in Africa as part of a joint project with Google.org, the philanthropic arm of Google.com.

Sample processing with 454 sequencing technology begins with random fragmentation of genomic DNA into 300–800 base-pair fragments and attachment of a DNA adaptor to the fragments to facilitate amplification, sequencing, and quantification. Each single-stranded DNA fragment in the library is immobilized on a capture bead and amplified in parallel via emulsion PCR, producing several million copies of the original fragment per bead.

Individual beads are loaded into the wells of a PicoTiterPlate device for sequencing. Earlier this year, 454 Life Sciences introduced the REM e System for the GS FLX, a robotic accessory module that automates liquid-handling functions for performing emulsion PCR and reportedly eliminates about five hours of manual lab work.

“In a single run we generate tens of thousands of clonal reads and can achieve unambiguous allele calling in less time and for less cost than conventional capillary electrophoresis genotyping methods,” said McLeod.

The workflow of 454 Life Sciences’ Genome Sequencer FLX System comprises four main steps that lead from one purified DNA fragment, to one bead, to one read. Generation of a single-stranded template DNA library is followed by emulsion-based clonal library amplification, data generation via sequencing-by-synthesis, and data analysis. The DNA library is immobilized on specifically designed DNA capture beads; each bead carries a unique single-stranded DNA library fragment.

Doing More With Less

Taking advantage of the ability of single-molecule sequencing technology to generate data from small quantities of nucleic-acid template and to generate epigenetic information, Helicos is collaborating with researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Broad Institute to perform chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies to identify epigenetic markers of chromatin structure. The model system being used for this research is inner cell mass from preimplantation mouse blastocysts, which gives rise to early stem cells. ChIP DNA derived from the inner cell mass is present in only picogram quantities.

In Helicos’ tSMS technology, labeled nucleotides are mixed with nucleic-acid templates immobilized on a flow cell. Detection of the fluorescent signals emitted as a result of each base addition is performed in the HeliScope™ Genetic Analysis System. The Helicos system can sequence 105–180 megabases/hour with average read lengths of 33–36 bases from templates ranging in length from 25 to 5,000 bases.

For direct RNA sequencing, the system can produce 300–400 million aligned reads/run with an average read length of 34 nucleotides (range 25–55) and a

In the system introduced by Pacific BioSciences, sequencing takes place on SMRT cells, each of which contains thousands of zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs). Each ZMW represents a hole tens of nanometers in diameter in a metal film that has been deposited on a silicon dioxide substrate.

The company describes each individual ZMW as a “nanophotonic visualization chamber” that serves as a window for observing the activity of the lone DNA polymerase molecule immobilized on the bottom surface of the ZMW. In this way the instrument can record the addition of each individual fluorophore-labeled phospholinked nucleotide in real time with a high signal-to-noise ratio despite the dense fluorogenic background.

Each labeled nucleotide emits a fluorescent signal that identifies the base being added to the growing DNA strand. The polymerase subsequently cleaves off the fluorophore, allowing the signal to return to baseline before the next nucleotide addition. Pacific Biosciences developed a method for nucleotide labeling in which the fluorophore is attached without interfering with the intrinsic speed, read length, and accuracy of the DNA polymerase.

Describing the ongoing challenge of detecting multiple target genes in the often-limited amounts of DNA present in patient samples, Alex Parker, Ph.D., principal scientist for molecular sciences at Amgen, presented the company’s nanoliter-scale strategy for creating highly multiplexed sequencing libraries by amplifying target genes derived from multiple patient samples to enable massively parallel sequencing using gen-2 sequencing technology. Amgen developed an adaptor-mediated reverse-nested PCR technique using the Fluidigm Access Array PCR platform to create a multiplexed sequencing library. This strategy eliminates the need for large panels of PCR primers.

The method involves attaching a universal tag to the 5´ end of the PCR primers, which allows them to mate with another set of primers that contain a multiplexing identifier and an oligonucleotide linker sequence. Amgen devised this method for use with the 454 Life Sciences sequencing platform and thus selected a specific linker sequence that would attach each member of the sequencing library to the beads used in the 454 system. The multiplexing identifier is, in essence, a barcode specific for each sample being sequenced that identifies the sample of origin for each DNA fragment sequenced.

By using a universal adaptor sequence, only one set of barcode primers is needed and each primer pair only needs to be synthesized once. The barcode primers can be reused and mixed with different sample DNAs in various combinations. For a multiplexed sequencing assay designed to analyze 100 different genes from 100 samples, for example, 200 primer pairs would be needed. This paradigm allowed Amgen to carry out the PCR reactions in small volumes on the Fluidigm instrument, with 35 nL reaction volumes, compared to a typical 10 µL reaction volume using conventional PCR technology.

“We have been able to scaledown the amount of input DNA,” using fewer “nonreplaceable research samples. Yet we typically get 5 percent more data per experiment compared to conventional PCR,” said Dr. Parker. This method yields faster results and reduces reagent volumes as well.

Dr. Parker and colleagues have also demonstrated that a high level of multiplexing is possible without significantly impacting the uniformity of the representation of PCR products in the final library. They are now applying this strategy to pathology samples, in which the DNA is often degraded due to the process of fixing the samples, and are working toward a standardized platform suitable for clinical applications.