A new study led by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) and UPMC Hillman Cancer Center has shown that an enzyme called PARP1 is involved in the repair of telomeres, the lengths of DNA that protect the tips of chromosomes, and that impairing this process can lead to telomere shortening and genomic instability that can cause cancer.

PARP1’s recognized job is genome surveillance. When it senses breaks or lesions in DNA it adds a molecule called ADP-ribose to specific proteins, which act as a beacon to recruit other proteins that repair the break. The new findings offer the first evidence that PARP1 also acts on telomeric DNA, opening up new avenues for understanding and improving PARP1-inhibiting cancer therapies.

“No one thought that ADP-ribosylation at DNA was possible, but recent findings challenge this dogma,” said Roderick O’Sullivan, PhD, associate professor of molecular pharmacology at Pitt and an investigator at UPMC Hillman. “PARP1 is one of the most important biomedical targets for cancer research, but it was thought that drugs targeting this enzyme only acted at proteins. Now that we know PARP1 also modifies DNA, it changes the game because we can potentially target this aspect of PARP1 biology to improve cancer treatments.”

O’Sullivan is senior author of the team’s published report in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, titled, “Deregulated DNA ADP-ribosylation impairs telomere replication.”

In normal cells, genomic lesions occur naturally during DNA replication as part of the cell cycle, and PARP1 plays an important role in fixing these errors. “ADP-ribosylation (ADPr) is a modification of macromolecules catalyzed by ADP-ribosyl-transferase (ART) enzymes known as PARPs that has a vital role in cellular physiology, but most pertinently in safeguarding genome stability through DNA repair,” the authors explained.

Healthy cells also have other DNA repair pathways to fall back on, but BRCA-deficient cancers—which include many breast and ovarian tumors—rely heavily on PARP1 because they lack BRCA proteins, which control the most effective form of DNA repair called homologous replication.

Although scientists discovered PARP1’s role in ADP-ribosylation of proteins about 60 years ago, O’Sullivan and his collaborator, Ivan Ahel, PhD, professor in the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology at the University of Oxford and world-renowned expert in PARP1, had a hunch that there was more to learn about this enzyme and its role in cells. “Although ADPr has long been considered solely a posttranslational modification of proteins, recent evidence for the ADP-ribosylation of nucleic acids, including DNA, challenges the established views of this modification,” the investigators noted.

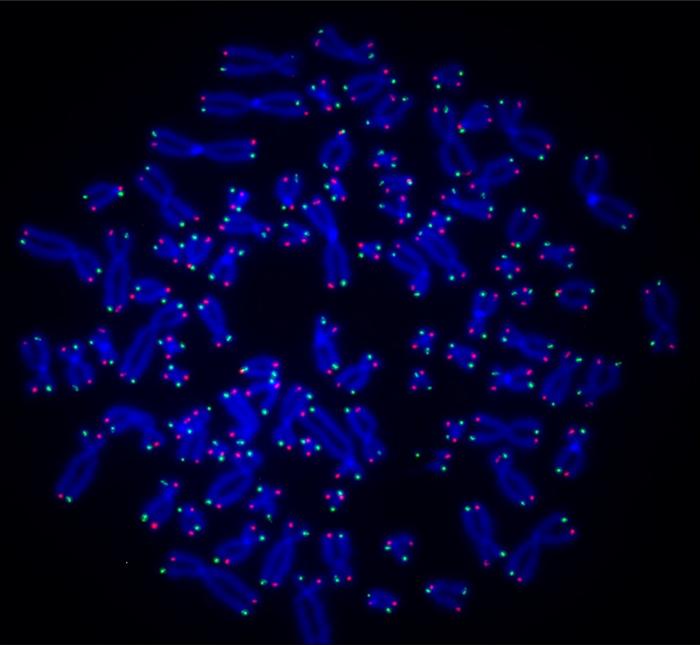

O’Sullivan and his team, led by Anne Wondisford, PhD, in Pitt’s medical-scientist training Program, first compared normal human cells with those deficient in PARP1. Using antibodies that bind to ADP-ribose and telomere-specific probes, they found that ADP-ribose attaches to telomeric DNA in normal cells but not in PARP1-deficient cells, showing that this enzyme is responsible for ADP-ribosylation of DNA.

Next, they compared normal cells with those deficient in another enzyme, TARG1, which removes ADP-ribose. They found that in the absence of TARG1, ADP-ribose accumulated at telomeres, leading to disruption of telomere replication and premature telomere shortening.

To show that these telomere defects were due to modification of telomeric DNA, O’Sullivan and his team took bacterial enzymes that function similarly to PARP1 and put them into human cells.

O’Sullivan said, “We used a guidance system to direct the enzymes to add ADP-ribose only at the telomeres and nowhere else in the genome. We found that if we load telomeres with ADP-ribose, their integrity is dramatically impaired, and it can kill the cell within days.” The authors further summarized, “… we identified that telomeric DNA repeat sequences are subject to PARP1-mediated ADP-ribosylation that is reversed by the ADPr hydrolase, TARG1 … That TARG1 must be disrupted to detect DNA-ADPr reflects that, like the protein poly-ADP-ribosylation, telomere DNA-ADPr is highly dynamic and subject to stringent control by TARG1.”

O’Sullivan hypothesizes that ADP-ribose affects telomere integrity by disrupting a protective structure called shelterin that safeguards telomeres, but more research is needed to confirm this. “… our study revealed that telomere DNA-ADPr is functionally and intricately linked with lagging strand telomere replication, and the failure to remove this modification due to TARG1 deficiency impairs telomere replication,” the team summarized.

“Targeting PARP1 has been a big success story for cancer therapy, but some patients develop resistance to PARP1 inhibitors,” added O’Sullivan. “I’m excited about this study because we’ve discovered something new about PARP1 biology, which generates a whole load of new questions that could help us develop novel approaches to target PARP1 or fine-tune therapies we already have. We’re right at the beginning of something exciting, and there’s a lot more to explore.”