![UC Davis researchers look for the underlying mechanisms as to why some food-borne bacteria cause illness. [NIH]](https://genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Frankengutbacteria21331863617-1.jpg)

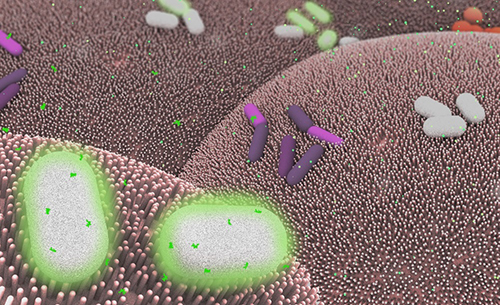

UC Davis researchers look for the underlying mechanisms as to why some food-borne bacteria cause illness. [NIH]

In an effort to understand the mechanisms governing pathogenic gut bacteria better, researchers at the University of California Davis School of Medicine inquired why some food-borne bacteria cause severe illness. In the results from their recently published study, the investigators describe how pathogens in the intestinal tract cause harm by benefiting from immune system responses designed to repair the very damage to the intestinal lining caused by the bacteria in the first place.

“The finding is important because it explains how some enteric pathogens can manipulate mammalian cells to get the oxygen they need to breathe,” explained senior study investigator Andreas Bäumler, Ph.D., professor of medical microbiology and immunology at UC Davis School of Medicine. “It also offers new insight into developing strategies targeting the metabolism of the intestinal lining to prevent the expansion of harmful bacteria in the gut, a situation that is exacerbated by the overuse of antibiotics.”

A normal, healthy large intestine is generally free of oxygen, and the beneficial microbes residing there thrive in this anaerobic environment. Conversely, enteric (intestinal) pathogens, such as Escherichia coli in humans or Citrobacter rodentium in mice, need oxygen to survive. The UC Davis team discovered how these pathogens change the gut environment to favor their own growth.

The findings from this study were published recently in Science in an article entitled “Virulence Factors Enhance Citrobacter rodentium Expansion through Aerobic Respiration.”

“Enteric pathogens deploy virulence factors that damage the intestinal lining and cause diarrhea,” Dr. Bäumler noted. “To repair the damage, the body accelerates the division of epithelial cells that form the intestinal lining, which brings immature cells to the mucosal surface. These new cells contain more oxygen and wind up increasing oxygen levels in the large bowel, creating an environment that allows gut pathogens like E. coli to outcompete the anaerobic-loving resident microbes.”

The research that Dr. Bäumler and his colleagues performed has important implications for developing new treatment strategies that target factors that compromise the intestinal lining function or bolster microbiota composition to offer either resistance or assistance to invading pathogens.

“The rise of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria has become a major public health threat worldwide, remarked Dr. Bäumler.”As more bacterial strains do not respond to the drugs designed to kill them, the advances made in treating infectious diseases over the last 50 years are in jeopardy.”

Just this past year the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified three drug-resistant organisms—Clostridium difficile, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae—as requiring urgent attention. Moreover, in May a report commissioned by the U.K. government predicted that by 2050 antimicrobial-resistant infections could claim 10 million lives a year and cost up to $100 trillion from the global economy.

Understanding how gut pathogens thrive and manipulate the body's natural defense mechanisms, while contributing to abnormal states within and beyond the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, is a burgeoning area of research at UC Davis. Scientists from schools and colleges across the campus are investigating antibiotic resistance as well as the influence that gut flora imbalances have on many conditions, including brain health and behavior, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, GI cancers, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver disease, autism, arthritis, and asthma.