Isobel Finnie Partner Haseltine Lake

Catherine Williamson Associate Haseltine Lake

When Priority Is a Priority

The CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing has been hailed as the biggest biotech breakthrough of the century. Some say it’s equivalent to discovering the structure of DNA or developing PCR. The CRISPR/Cas9 system promises a precise, relatively simple, and versatile method for introducing targeted modifications into DNA. Already, investment in this technology has been huge due to its wide applicability in the lab and possible role in eradicating genetic disorders in humans and other animals.

The question of who owns and can control the use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system is consequently of pressing importance and is under intense debate. It is claimed to have been developed independently by two separate research groups. Both groups sought patent protection and published data from their work, creating a complex IP situation as the patent filing and article publication dates are closely interwoven.

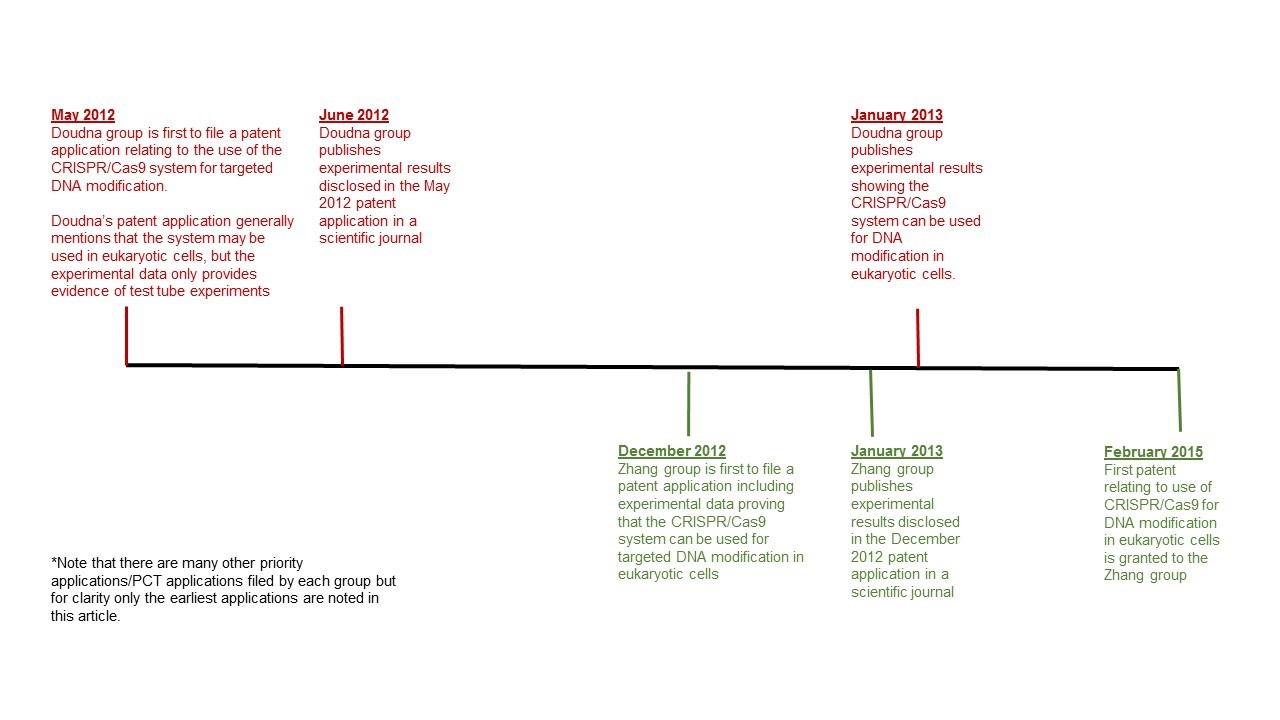

A research group led by Jennifer Doudna at the University of California, Berkley (UCal), was the first to file a patent application on the use of this system for targeted DNA modification in May 2012, and the first to publish experimental results reporting in vitro use of a single-molecule guide RNA in a CRISPR/Cas9 system for targeted DNA cleavage in June 2012.

Another group led by Feng Zhang at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard was the first group to publish experimental results showing that this CRISPR/Cas9 system can be used for targeted DNA modification in eukaryotic cells in January 2013, shortly after filing their earliest patent application on this system in December 2012.

After the Zhang group’s January 2013 publication, but still in the same month, the Doudna group also published evidence that the system works in eukaryotic cells. The Zhang group was, however, the first to obtain a granted U.S. patent after requesting acceleration of the examination process at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

A key feature of the U.S. debate is over which research group was the true first inventor of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, especially its use in eukaryotic cells. At the time the first patent applications were filed, the U.S. had a “first-to-invent” system—which means the first person to develop an invention is entitled to have the patent, even if they were not the first to file a patent application (or the first to get a patent granted) for that invention. UCal has started “interference proceedings” against the Broad Institute to determine who was the first to invent the CRISPR/Cas9 system. UCal claims that they were the first to invent the use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system for gene editing, and that their earliest patent application enabled gene editing in eukaryotic cells. In contrast, The Broad Institute are arguing that UCal had not invented the use in eukaryotic cells at the time of filing its first patent application and are therefore claiming that The Broad Institute were the first to invent the use of CRISPR/Cas9 in eukaryotic cells. These proceedings are still ongoing.

So far, UCal has no granted European patents on this technology. But this hasn’t prevented other parties attacking UCal’s patent position using “third party observations”—a pre-grant way for third parties to object, sometimes anonymously, to a European patent application. Third-party observations most commonly relate to novelty and/or inventive step, but may also relate to clarity, sufficiency of disclosure (whether the application would have provided a person of ordinary skill in the art to perform the invention at its earliest filing date), and unallowable amendments. It can be a good way of getting the European Patent Organization (EPO) to consider certain issues, since the EPO should take these observations into account and incorporate any objections they agree with into their next written communication with the applicant.

UCal’s first patent application in Europe has now attracted the unusually high number of nine different sets of pre-grant third-party observations. The most recent of which were filed in December 2016, after the applicant addressed some formal matters which had appeared to be the last hurdle in the progression toward granting the patent. This prompted UCal to respond, arguing that those most recent third-party observations related only to matters already considered by the EPO, and that the EPO must not allow repeated filing of third-party observations to be used as a mechanism to prevent patent grant. It will be interesting to see whether the EPO now changes its opinion on the allowability of this patent.

One of the points of objection to UCal’s European patent application is whether or not the priority date is valid. One question is whether UCal’s earliest patent filing in the U.S. describes the invention in enough detail, since that document did not describe certain DNA sequences, called PAM sequences, which are important for the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Loss of the priority date would likely be a serious problem. At present, the EPO appear to accept UCal’s position that the earliest patent filing in the U.S. did provide enough information. A similar challenge would be: whether an ordinary skilled person would have been able to perform the invention in eukaryotic cells at the earliest filing date, given that this had not yet been shown to work at this date.

With that pre-grant context, we can be sure that when UCal gets a granted patent it will be the target of multiple, strongly fought oppositions. Oppositions are a post-grant way for third parties to object to the grant of a European patent. It is possible for one party to file both third-party observations and an opposition against the same patent. An opposition must be filed within nine months of the patent grant and can relate to issues like novelty and inventive step. Although the grounds of opposition are slightly restricted compared to those available for third-party observations, e.g., clarity cannot be objected to. During the opposition procedure, each of the opponents and the patent proprietor get to provide written submissions; and the process ends with an oral hearing to argue the case before an opposition division consisting of at least three people who will make the decision. To date, at least seven European patents have been granted to The Broad Institute (Zhang’s group) and each of those patents to have reached nine months from grant have attracted multiple oppositions.

One of the principle lines of attack in the opposition proceedings against The Broad Institute’s first granted European patent (EP2771468) is lack of novelty and/or lack of an inventive step over UCal’s earlier-filed first patent application (filed in May 2012) and their June 2012 publication. The decision on novelty will likely come down to a comparison of the precise wording in The Broad Institute’s granted patent and the wording in UCal’s first patent application. In relation to inventive step, the opposition division at the EPO will have to decide whether it would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art that the CRISPR/Cas9 system could be applied to eukaryotic cells, in view of UCal’s publication of their in vitro experiments. This can be seen as the mirror image of an argument described above that will be levelled at UCal.

The Broad Institute is also facing objections on whether or not their priority claim is valid. In this case, the problem is that the named applicants on The Broad Institute’s earliest patent filing in the U.S. were not the same as the applicants named on the later patent filing that became the European patent—which is a requirement. Once again, loss of the priority date is likely to be a serious problem.

We can therefore expect the European CRISPR/Cas9 patent wars to continue to be fiercely fought and to continue to include a growing number of patents. Whilst the specific legal challenges used in Europe are different from those in the U.S. (and in particular have highlighted how important a correct, valid priority claim can be) similar scientific arguments are used on both sides of the Atlantic. A huge field of research and potential medical advancement is waiting to see the outcome of these patent wars and, thereafter, how the victors will assert their patent position.

The CRISPR patent wars are being intensely fought in Europe as well as in the U.S.

Isobel Finnie ([email protected]) is a partner and Catherine Williamson ([email protected]) is an associate at Haseltine Lake.