January 1, 2011 (Vol. 31, No. 1)

Editor’s Note

GEN turns 30 in 2011, and we invite you to join the celebration. We have a number of events and activities planned throughout the year, so be sure to look out for them.

One special feature will appear regularly throughout 2011. We will reprint an article from one of GEN’s earlier issues because of its particular importance and relevance to the development of the biotech industry. The article will appear in the print issue of GEN as well as online. We encourage you to comment on the article on our website, www.genengnews.com, based on the topic, issues, and technologies discussed.

One of the most notable articles to appear in the very first issue of GEN was entitled “Ptashne to Go Without Harvard U.” The story took place at an extremely early and critical stage in the evolution of the biotech industry. Two major points pop up in the article: 1) the initial reluctance by major universities and academic centers to become involved in commercial biotech activities, and 2) local community fears about having a genetic engineering laboratory in the neighborhood.

Some of the questions you may want to respond to are: Do you think there are still people in academia who view the business of biotech negatively? If so, why? Can you provide some examples? In retrospect, do you believe the close community scrutiny that new biotech labs received 25–30 years ago while they were being built were justified or an over-reaction on the part of people who did not understand the technology?

These are just a few suggestions that you might want to address in a comment to the article. There might be other issues raised by the article that you may want to discuss. Come on! Join the GEN 30 Celebration!

P.S. Genetics Institute was bought by Wyeth (now Pfizer) in the late 1990s and is now part of that company’s research division.

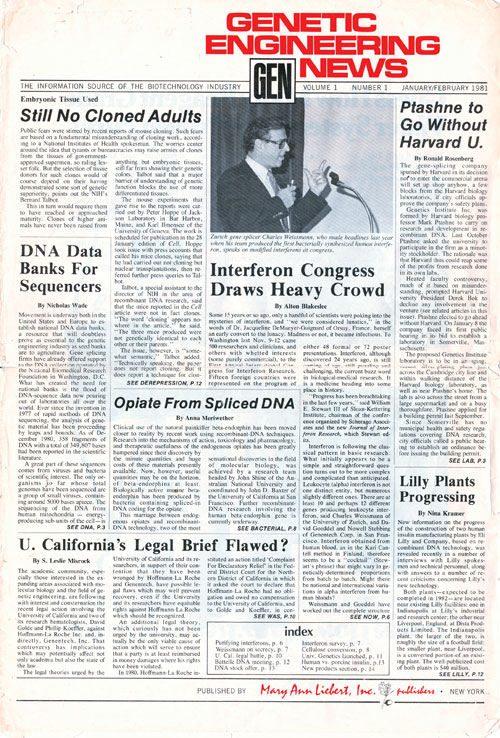

“As Seen in GEN” Volume 1, Number 1, January/February 1981

Ptashne to Go Without Harvard U.

By Ronald Rosenberg

The gene-splicing company spurned by Harvard in its decision not to enter the commercial arena will set up shop anyhow, a few blocks from the Harvard biology laboratories, if city officials approve the company’s safety plan.

Genetics Institute, Inc., was formed by Harvard biology professor Mark Ptashne to carry out research and development in recombinant DNA. Last October, Ptashne asked the university to participate in the firm as a minority stockholder. The rationale was that Harvard thus could reap some of the profits from research done in its own labs.

Heated faculty controversy, much of it based on misunderstanding, prompted Harvard University President Derek Bok to decline any involvement in the venture. Ptashne elected to go ahead without Harvard. On January 8 the company faced its first public hearing in its bid to establish a laboratory in Somerville, Massachusetts.

The proposed Genetics Institute laboratory is to be in an aging vacant silver-plating plant just across the Cambridge city line and within walking distance of the Harvard biology laboratory, as well as near Ptashne’s home. The lab is also across the street from a large supermarket and on a busy thoroughfare. Ptashne applied for a building permit last September.

Since Somerville has no municipal health and safety regulations covering DNA research, city officials called a public hearing to establish an ordinance before issuing the building permit.

Several people expressed fears of organisms escaping from the laboratory that could be carried from one building to another, such as the supermarket, by cockroaches and rodents. Others were concerned about potential vandalism and theft of dangerous materials as well as the hazards of such materials. A few suggested that criminal sanctions should be included in the ordinance. One woman, fearful of new “creatures”, said “scientists are generally unfit mothers.”

No area residents endorsed Genetics Institute. Instead, most called for very strict health and safety controls. A few, including the former Cambridge mayor, said Genetics Institute should contribute some of its profits to the community, since the original research at the university was done with federal tax dollars.

To allay their fears, Ptashne explained that weakened Escherichia coli bacteria are used with genes added to make proteins of medical value, such as insulin. “You cannot turn a harmless bacterium into a dangerous one,” Ptashne said politely.

Backing him up was Bernard M. Fields, chief of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s hospitals in Boston and professor of microbiology at the Harvard Medical School. He stressed that there was little possibility of rodents “colonizing diseases from Genetics Institute. They [the company] are not starting with dangerous pathogens,” he said. Fields added that the company’s work is less hazardous than a clinical laboratory or a hospital, where cultures of meningitis, salmonella, and influenza are taken from patients.

Somerville officials have proposed an ordinance patterned after Cambridge’s three-year-old regulation covering DNA research at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Somerville officials, however, were considering going beyond the Cambridge ordinance by banning work done at the more dangerous P-3 and P-4 containment levels.

While Genetic Institute would operate at the P-1 and P-2 levels, the company does not want to be arbitrarily restricted. “We will do work in P-1 and P-2 levels, but to be told that we never could to P-3, well, we wouldn’t go ahead,” Ptashne told city aldermen.

Whether Genetics Institute gets permission or not, it is starting out with more than $3 million from some of the most prestigious investor and venture-capital firms. Among them is William Paley (CBS Inc., chairman), Venrock Associates of New York (Rockefeller family money), J.H. Whitney Co. of New York, and Greylock Management Co. of Boston.